The Future is Female: Women must support other women to enter politics

February 12, 2017

On election night, as the rest of the country was gearing up for either despair or celebration, in the small Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis, a new face was quietly elected to the Minnesota State House of Representatives.

Her name is Ilhan Omar, and she is the first Somali-American legislator in the country. Omar fled Somalia with her family at the age of 8 and lived in a Kenyan refugee camp for four years before coming to the United States.

In other parts of the country, the first Latina and South Asian women were elected to the U.S. Senate, and the first Vietnamese-American woman ever in Congress was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Last week here in Boston, a Somali woman, Deeqo Jibril, announced her plan to run for City Council.

The reason it’s taken 115 Congresses to elect a Somali, Latina, South Asian or Vietnamese woman is not because there are no Somali, Latina, South Asian or Vietnamese women in the U.S. It is because the systems in place in this country discourage women from entering the political sphere. That battle, one women have been fighting for hundreds of years, cannot end when the polls close on Election Day.

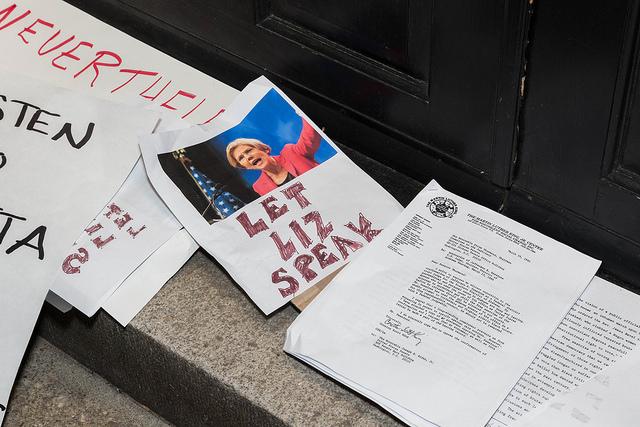

In a 2014 study surveying 171 female state legislators released by Political Parity, a nonpartisan group looking to increase female participation in politics, three in four survey respondents said they felt discriminated against in political life. This discrimination was keenly felt in the Senate last week, when Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) was silenced while reading a letter written by Coretta Scott King.

Three Democratic senators, all men, were able to read the letter after the Senate silenced Warren and even enter it into the congressional record without objection. Warren was the only one who was silenced, and she was silenced because she was a woman speaking out.

In Political Parity’s study, one of the authors, Heidi Hartmann, said that unlike in other professional fields, there are no widespread training programs for politics that help increase gender equity. That’s where our work needs to start.

Before Omar was elected, she was the director of policy for the Women Organizing Women Network, a local Minneapolis-based group helping East African women run for civic and political leadership. In order to decrease the gender disparity in politics, we need work like Omar’s to continue. We can start right here in Boston by encouraging Jibril’s bid for City Council and lifting up her community’s voice.

Like Jibril, there are so many women out there who could effect change in their communities but lack the support or resources to mount a political campaign. We need more community organizations and volunteers doing the dirty work between elections—overcoming years of oppression to help women do what’s always been in the back of their heads: What if I ran for office?

Emily’s List, a national organization training pro-choice Democratic women to run for office, is one group doing this work. But we need more women, starting from the ground up, advocating and providing resources for marginalized communities of women who are the most underrepresented in government.

Local and national organizations already exist, like Emerge Massachusetts, a local chapter of the national Emerge America movement, and VoteRunLead, another national organization. Still, we need more groups like Run for Something, which promotes young people running for down-ballot offices, and we need more grassroots movements.

The next elections will take place in 270 days. There are young women in classrooms, dorms and offices in Massachusetts, Minnesota and across the country, scared for their futures. We need someone to tell them that they can change their circumstances—and that there will be a national, even global, community of women to back them up.

Photo courtesy Lorie Shaull, Creative Commons