Review: ‘Black Panther’ is black excellence that hooks the world

March 6, 2018

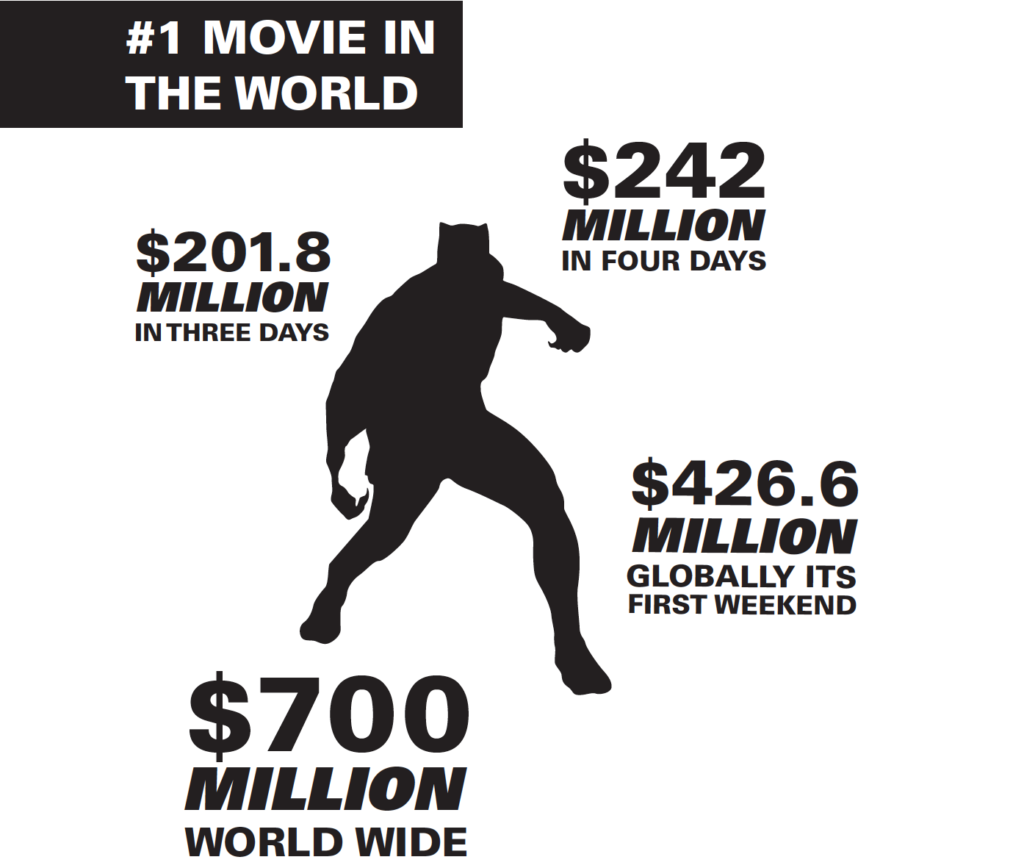

Now the number one movie in the world and holding the highest rating of any film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe franchise, “Black Panther” has the world captured within its claws.

“Black Panther” is only the fifth movie to debut with more than $200 million its opening weekend and now holds the second highest U.S. box office record set over four days. The groundbreaking film surpassed low-ball projections for a record $426.6 million globally its first weekend, breaking yet another record. As the second weekend came to a close, the film’s roaring economic gain crossed $700 million worldwide.

Rather than ask why “Black Panther” has garnered so much success, the better question is: What took Marvel so long?

Historically, black heroes in Marvel movies are sidekicks. They have always filled supporting roles — the token characters that exist solely to enhance the hero. For decades, the person of color sidekick trope has marred Marvel’s history as one that has lacked diverse superhero characters.

“Black Panther” is political, but not in a way that divides. Rather “Black Panther” educates and unifies viewers. The script has flipped — white characters now exist solely to enhance the stories of more nuanced black characters. CIA agent Everett Ross, the one “good” white guy in the film, mainly serves as a comedic footnote to the cinematic journey “Black Panther” takes viewers on. To Ryan Coogler’s credit, Ross becomes a hero in his own right for helping Wakanda — the African nation where most of the movie takes place — without being a white savior.

Although there is debate as to whether or not the black empowerment in this film challenges racist narratives, “Black Panther” sent a message that has resonated across the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the media industry and pop culture. “Black Panther” isn’t like any other trip to the movies — it is a celebration of black excellence to a community that has long awaited this embrace of diversity and representation.

With stunning cinematography, thrilling action scenes and relevant racial commentary interwoven into a well-crafted plot, “Black Panther” is a film the whole world should see. Made as a film about black people, by black people, for black people, one of Coogler’s greatest achievements is the creation and portrayal of Wakanda itself.

In an appearance on The View, Lupita Nyong’o, who plays Nakia in “Black Panther”, touched upon how Wakanda helped demonstrate Africa’s global narrative in a different light.

“We come from a continent of great wealth, but a continent that has been assaulted and abused…and exploited. Colonialism… rewrote history and changed our narrative. Our global narrative is one of poverty and strife, and the wealth of the continent is very seldom seen on such a global scale…” Nyong’o said.

Although Wakanda is fictional, Nyong’o said the civilization reimagines an Africa without the consequences of colonialism.

“Wakanda is special because it was never colonized, so what we can see there for all of us — it’s a reimagining of what…would have been possible had Africa been allowed to realize itself for itself,” Nyong’o said.

The film follows events from “Captain America: Civil War” — the movie that introduced the Black Panther into the Marvel Cinematic Universe in 2016. In the film, T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) is prince of Wakanda and next-in-line to be the Black Panther and king. His father T’Chaka (John Kani) is killed in a terrorist attack that fuels the rest of the story’s plot line, as T’Challa attempts to avenge him amid internal clashes between Avengers. This is where “Black Panther” picks up, as T’Challa assumes the throne and sole power of the Black Panther strength.

A heart-wrenching revelation changes T’Challa’s image of his father. This betrayal traces back to Erik Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) and Ulysses Klaue (Andy Serkis), the two antagonists of the film who start off the film as allies. Their criminal partnership, based off an interest in Wakandan vibranium — the most powerful, fictional metal — does not last long. Killmonger kills Klaue to become the sole threat to Wakanda and T’Challa’s throne.

What is perhaps an unintentional fault – that nonetheless enhanced the film – was the convergence of both T’Challa and Killmonger’s stories that resulted in what felt more like Killmonger’s origin story than T’Challa’s journey to the throne.

But let’s talk about the brilliance of Michael B. Jordan’s character, who is another achievement in Marvel’s first blockbuster featuring a black superhero and an almost entirely black cast. Director Ryan Coogler took “a kid from Oakland who believes in fairytales” to shape the simplest and most effective base for Marvel’s best villain to date.

Born with the Wakandan name N’Jadaka, Erik Killmonger is both the black American and human perspective Marvel has lacked. This villain, in addition to having relatable motives, leaves a profound impact on T’Challa. In fact, Killmonger’s influence on T’Challa’s worldview prompts the king to change Wakanda from being an isolationist country to providing international aid and sharing their technological developments with the world.

Erik Killmonger is a manifestation of the unrestorable cultural wound that colonialism and slavery left on the black American man. The only critique I have is that Coogler devalued Killmonger’s life. In a film about black empowerment, Erik Killmonger, a black American, is the only black person who is neither empowered or redeemable.

Abandoned and betrayed by his family and nation, Erik Killmonger is just another member of the black population outside Wakanda that represents the truth King T’Chaka “chose to omit.” The truth is that Killmonger was right to say Wakanda failed the world around them by hoarding its resources, but Coogler blanketed global domination and destruction over Killmonger’s better intentions to portray him as corrupt.

This mistake paints Killmonger as a black American “thug” who is the most dangerous threat to Wakanda, and thus the world. This makes Killmonger seem as though neither him and what he represented were not worth saving.

In his final scene, as Killmonger dies from a wound by T’Challa’s spear, he refuses to be saved by Wakandan technology T’Challa offers him. The refusal comes from the mere fact that Killmonger knows the score — just as black American men do concerning incarceration — which is all that T’Challa offers.

Recalling his ancestry, Killmonger’s final words are: “Nah, just bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships. Because they knew death was better than bondage.” There is a pause, and it is in this pause that the real tragedy of Killmonger is felt, but more so in Coogler’s missed opportunity.

Although T’Challa reconciles with the fact that Killmonger is right, T’Challa does not redeem Killmonger himself. Thus T’Challa’s chance to dispense the justice Erik Killmonger never received is left unseized. Killmonger’s awareness of his impending incarceration mirrors the all-too-real awareness black American men have of the disproportional rate at which they are imprisoned. T’Challa’s offer of this incarceration is one Killmonger will never take. So his death is another that mirrors that of black men who face unjust deaths in the United States. As Christopher Lebron argues, “Killmonger yanks the spear out of his chest and dies. The sun sets on his body as it did on Michael Brown’s.”

Nonetheless, I must praise the way Ryan Coogler handled the question of violent resolution. Superhero movies could learn from “Black Panther.” The manner in which Coogler undertakes the film’s violence is innovative and did not make a spectacle out of black people killing one another.

“Black Panther” never was and never will be like any other comic book superhero movie. King T’Challa symbolizes the black struggle against oppression. “Black Panther” co-star Winston Duke, who plays M’Baku, commented on the symbolism behind T’Challa’s powers.

“Your hero is using kinetic energy that’s meant to harm him, and he redirects it and uses it as his power — if that’s not an allegory for oppressed people, I don’t know what is.” Duke said.

For the black community, the film is a testament to representation that reflects beauty, strength, and success. For young black girls, the film shows they can grow up to be on the big screen, that women as dark as they are can take the world by storm. They can grow up to be powerful, resilient and multifaceted like Danai Gurira as Okoye, Lupita Nyong’o as Nakia and Letitia Wright as Shuri.

For young black girls, the princess they have been waiting for is Shuri. Shuri is not only a sixteen-year-old princess, but is a black, female scientist who heads all the technology in the wealthiest and most advanced civilization in the Marvel universe. For black women like me, the film fulfills a life-long dream to see strong black women front and center as warriors who are more than capable of saving the world all by themselves. They are, at last, “the heroes of their own stories,” as former First Lady Michelle Obama tweeted.

Coogler brilliantly employs the powerful women in the film to navigate the storyline and ultimately reinforce that they are Wakanda’s most important forces. When the Wakandan throne is turned over to Killmonger, it is Nakia and Queen Mother who unify Wakanda with the Jabari, the Wakandan ethnic social outcasts.

Angela Bassett, who plays the Queen Mother (T’Challa’s stepmother), asserted that women’s roles in “Black Panther” reflect how they are viewed in African nations. “[T’Challa] can’t do it without them,” she said, adding that there can’t “be a king without a queen.” “Black Panther” demonstrates that films can be pro-women without having to be anti-male, and better yet, it finally acknowledges the power of black women rarely recognized in history, society and media.

This is seen in Danai Gurira’s character Okoye’s most poignant scene — her last before the credits rolled. General Okoye, head of the Dora Milaje, the all-female Wakandan special forces, unflinchingly stood in front of her opponent — her love interest W’Kabi (Daniel Kaluuya), who made himself and his men enemies by supporting Killmonger’s coup d’état.

“Drop your weapon,” she orders. Shocked, W’Kabi asks, “Would you kill me, my love?” Okoye responds, “For Wakanda?” She pauses before expertly twisting her spear so it is pointed at him, then asserts emphatically: “Without question.” W’Kabi’s response is wordless. He drops his weapon first, then falls to his knees in front of her. All the men of his tribe follow suit, kneeling before the women of Wakanda in surrender.

This moment is unspeakably valuable — as the visual of seeing anyone, especially a black man, submit to a black woman on such a large screen is rare. “Black Panther” cherishes the great power black women possess; Wakanda doesn’t envision a world where women can live up to all they are, rather it is a world where women are allowed to live up to their full potential.

Beyond displaying black women at their full potential, “Black Panther” shows a society in which gender equality reigns. The powerful message seen by audiences all over the world is that a civilization can function wholesomely with “men and women… living in their power without one dwarfing the other,” as Lupita Nyong’o affirmed in her sit-down with Entertainment Weekly. There is no doubt that sexism is learned, but what Wakanda shows is that when gender equality is interwoven into the fabric from which a society is built, it is possible for the delineations of sex to not be oppressive.

My generation may not have grown up with the privilege of seeing superheroes and princesses of color represented in the same way as white ones, but my younger sister’s will. “Black Panther” is just the beginning, and communities of color have waited long enough. Every generation after us will know this film — it will inspire what comes next: people of color gracing the biggest roles across the media industry and pop culture, which have otherwise been monotonously occupied by white men and women. Those white men and women will now share the screen with their equally worthy counterparts of color.

For all people of color, the unprecedented success of “Black Panther” is a promise of diversity, proving that not only can black stories become global blockbusters, but that they are worth telling. Black stories matter, and “Black Panther” highlights the power behind emphasizing that within those stories, black lives matter.

Above all else, “Black Panther” was a love letter to children of color, specifically black children. “This film is a godsend that will lift the self-esteem of black children in the U.S. and around the world for a long time,” wrote CNN’s Van Jones, characterizing “Black Panther” as a “better future” that beckons. I would argue that “Black Panther” beckons to a generation of children who are the future.

In dark times, this film by directing genius Ryan Coogler — and soon Ava DuVernay’s “A Wrinkle in Time” — gives the world a cinematic experience that shows black boys and girls that they hold the power to decide who they want to be in life. They hold the power to shine.

“Black Panther” was revolutionary in many ways, but perhaps most impactful was how it allowed a minority community to not only envision an excellence that has always existed, but to finally see it on display for the world to appreciate. Decades from now, we won’t be talking about Captain America or Thor — we’ll still be talking about “Black Panther.”

So long live the king… and more importantly, #WakandaForever.